Chimerical

Shiftings / Chimerische gestalten (of een aanzet tot mythomanie)

|

|

|

Published in Dutch

in Mba Kajere magazine in 1996. Association of ideas about gender. Chimerical Shiftings (or an initiation to mythomania)

(Dutch

text below) People favor

unambiguousness and uniformity. There is nothing as irritating as someone who

systematically breaks with prevailing codes and who causes a continuous

confusion in circles of family and friends, but particularly within the

structures of society. Take for example Janine Wegman, a well-known Rotterdam

transsexual, who wanted to renew her passport, and, due to automized

bureaucracy, found herself a man again. Yet she is not even an example of a

provocative genderbender: for many years now she maintains a monogamous

heterosexual relationship with her male partner. With the

rise of new communication systems like Internet, the possibility is created

to chose an identity in a physically less intervening manner. Man, woman,

animal, plant, machine, nothing stands in our way to become per day or per

second the avatar which suits us at that moment. And all this without

expensive operations or otherwise far-reaching consequences. But can you, in

the case of the transsexual or the cyber-genderbender, speak of a new

identity? Is it currently at all possible to consider an identity or even a

non-identity as 'truthful'? Identity, fiction, myth The Austrian

writer Elfriede Jelinek stresses in an interview the impossibility for women

to assume a subject status on a linguistic level.[1]

She points out the consequences this has for the description of feminine

lust. Even in a dominant role the female remains an object: that is to say a

masculine projection. Jelinek therefor must assume the non-identity of the

female. For a woman who wants to be accepted as a writer amongst her male

colleagues this position is understandably unacceptable. The woman as creator

of new concepts is and remains a generic-based difference. At best the

phallocentrism is replaced by 'vagina-centrism'. Patricia de

Martelaere rethinks the works of Friedrich Nietzsche - who has been noted as

a very misogynic thinker - in an interesting critical reading. She calls

Nietzsches misogyny into question and ascribes to women an almost

paradigmatical position: "What the female means to the male is in fact a

model for what the whole reality means for the yearning mortal; she is a

fascination, a challenge and a promise; she is an enchanting game of shadows

with the suggestion of a dazzling light; she is inconsistent, blinding and

tiring - but in the end she is nothing (...) It is in this sense that to

Nietzsche the woman, the being which has

no truth and also does not want to know

truth, is on the philosophical level precisely the incarnation of his own

idea of truth."[2]

Concluding she states that the generic model for Nietzsches gay science is neither that of man or

woman, but of the hermaphrodite, which she sees as the contradiction within the individual. Lieven de

Cauter discusses in Archeologie van de

kick the hermaphrodite from a semiotic point of view. He ascribes a

signifying value to the hermaphroditic: "The hermaphrodite is the

personification of the neutrum, the

'non of both', the neuter (...,) the neutral signifier."[3]

Or as de Cauter writes referring to Jacques Derrida:"The empty

signifier, vacant, brittle, changeable, useless."[4]

According to him the hermaphrodite is the main example of an empty signifier:

"He breaks with the principle of identity, the historical base of our

binary logic: the principle of identity (a=a), the principle of the excluded

third (something is either a or not-a), the principle of contradiction (a=

never not-a). (...) He 'signifies' in the end nothing else than that he is

neither the one nor the other. And yet he is also the Fata Morgana or 'both at

the same time', the mythological form of the dialectical synthesis."[5] For the

moment I will leave it an open question as to whether this is a dialectical

synthesis or not. Important is the positivity of the equivocality, the

ambivalence. In these

interpretations the hermaphrodite can offer a perspective on modes of

existence which oscillate in the tension between a (male) identity and

non-identities. It would not be a question of creating a new (opposing) truth

but of generating other options, perhaps fictions. But what is

fiction nowadays? Let me go back to our cultural heritage: the myth. Isn't

the myth the contemporary example

of fiction? A myth is a tale about the deeds of gods, demi-gods or divine

ancestors which is set in a mythical primeval age in which the world reveals

itself. A myth cannot be fitted into historical time or geografical space:

only through ritual can it be placed in time and space, as a collectively

transmitted experience. In this way the myth creates a collective identity. What

happened to the myth? In Greek times the mythical interpretation was

gradually taken over by reason. This did not necessarily have to lead to

conflict: to Aristoteles the true 'philosophos' was still a philomythos. The

sophists however had already put the word 'mythos' against 'logos'. Its truth

is determined by rational proof, the best argument. In the development of

Western thinking, based on the notion of the accumulation of knowledge, the

myths only have meaning in a historical context. A 'myth ' is then nothing

but an unmasked fable, a tale, an untrue story. Nevertheless,

how untrue is the myth in a world which becomes more and more aware of the

idea that accumulation of knowledge will not lead to final coherence, to an

absolute truth. Or, as Jean François Lyotard states, a world in which every

trust in all-encompassing legitimizing discourses has been scattered and the

supposed religious, ideological and scientific truths turned out to be just

appearances. I would like to, going from Nietzsches remark in Gőtterdammerung about how the

'true world' turned out to be a fable and his conclusion that with the true

world we also abolished the apparent world, make a proposal to a mythical

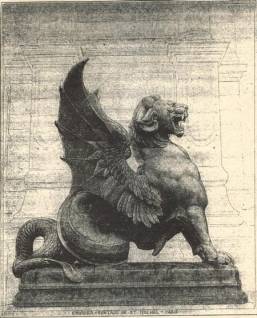

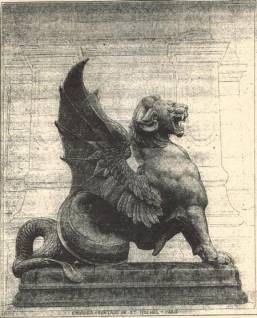

identity. Chimera: from a mythical beast

to perverse femininity "At the

beginning of the world, living and imaginary, there is a double wedding:

Mother Earth weds her son Heaven and her son the Sea. The first marriage,

which is fruitful and harmonious, a love match, produces a line of gods and

kings (...) The other marriage - the union between Gaea and Pontus - which is

a discordant one (between the fruitful earth and the unfruitful sea),

produces instead, a line of monsters and prodigies, of brothers and sisters,

along a horizontal axis dominated by two factors: seriallity and

hybridization."[6] The Chimera,

a great-grandchild of Earth and Sea is a unique beast which consists of parts

of three animals. One of the most clear descriptions is by

Appolodorus:"It had the fore part of a lion, the tail of a dragon, and

its third head, the middle one, was that of a goat, through which it belched

fire. And it devastated the country and harried the cattle; for it was a

single creature with the power of three beasts."[7]

From ancient times, like for example the Ilias,

the Chimera is described only in the context of her death: she has been

slaughtered by Bellerophon, who later meets his fate due to his

overconfidence. Ginevra

Bompiani makes in The Chimera Herself

an interesting connection between the word 'hubris', the sin which causes

Bellerophons downfall and 'hybrid', the word with which the Chimera is

described. She states that Bellerophon, through killing the Chimera, at the

same time destroys what Chimera has come to represent through the ages:

fantasy, poetic genius, dream, illusion, fiction.[8]

In the myth

of the Chimera two important elements stand out: her multiplicity and her

illusionary quality. These evidently have something to do with each other.

They feed a deep-rooted fear within Western culture which Paul Diel has

forcefully put into words: "The myth externalizes the danger in the form

of a monster encountered by chance. In truth the chimerical enemy is always

present; every man secretly carries within himself the temptation of

imaginative exaltation - that is the devouring monster, Chimera. It is clear

that 'chimera' and 'perverse imagination' are synonymous."[9] Through the

ages the Chimera and her disturbing connotations underwent a transformation

from myth to sign. In modern times she is metaphorically conceived of as the

bad muse, as a perverse feminine principle. Like in Flauberts Par les champs et par les grèves where

she represents omnipotence and nihilism at the same time: everything is

possible, nothing is important. Through her unlimited possibilities she

becomes as meaningless as Derrida's signifier:"In the last decade of the

nineteenth century, the image of the Chimera has become for poets and

writers, as for painters a metaphor for an enigmatic feminine principle which has the power to attract,

conquer and annihilate the power of the artist"[10]

In short, the Chimera seems to be a perverse feminine principle which holds

no identity, but is interpreted as an illusionary compound of shifting

identities. Chimera as a nomadic action Can this

mythical animal express ways of existence in our contemporary 'postmodern'

era? Can it mean more than what one can find in encyclopedia and dictionaries

as mythological beast, biological hybrid, psychopathological fantasy? Are

there, bringing back to memory the feminine position as a non-identity in the

beginning of my argumentation, similarities with this position? Is a possible

unequivocal reference to the feminine being surpassed? In any case here the

feminine does not stand against the masculine. She is at most a constantly

shifting 'perverse' principle, which crosses every unity: "In other

words, she contains the power to nullify any attempt at making sense and to

discourage any renunciation of it."[11]

Precisely this ambivalence makes her an empty signifier, which seduces the

thinking - in vain - to create new unambiguous meanings. Maybe we recognize

in Gilles Deleuzes thinking - he has also been inspired by Nietzsche - an

attempt to turn the Chimera into a way of thinking. According to Deleuze

Nietzsche tries to execute a decoding on the level of thinking and writing of

existing codes, this means absolute decoding or in spatial terminology:

deterritorialization. He uses the beautiful image of Kafka's The Chinese Wall, of Nomads who

besiege the city. It's the image of a nomadic warmachine that stand against

the despot with his governmental machine. The despot wants at all costs to

integrate the nomadic machine. He repeatedly wants to fixate the codings.

Important in this is that Deleuze generates a way of thinking which surpasses

the existing codes again and again. Deleuze shows that unambiguous meanings

are mere constructs. They are necessary for thinking, but impossible as

absolute truths. A chimerical way of thinking could incorporate openness

which is 'characteristic' to this thinking. What, for

example, can it state about the developments in the field of Internet, as

mentioned in the introduction. Does it open a perspective for an estimation

of the effects of the digital media? Genderbending does not necessarily need

to be looked upon as a game with the hybridity of a given identity. It is

more a chimerical principle of 'cyberspace': the loss of fixed positions of an active producer and

a passive consumer, through which a shifting of positions take place. One can

also find chimerical shiftings in the (digital) art work: heterogeneous

elements (visual, audio, tactile, etc.) which are brought together in

installations in which the experience of an unequivocal harmony between body

and mind shifts all the time. The recipient becomes producer, the producer

recipient in the effects of the medium. The oscillation between the

subject-object opposition, literally through inter-action, makes the producer

as well as the recipient part of 'the' art work. Her is not important whether

something new is happening or not. Perhaps the conceptualization of it

reveals something which has been happening within our collective experience

all the time. The

physical effects of these interactive experiences, which are not so much

caused by but laid open through recent developments, are in my opinion highly

interesting. How are we going to experience 'our' bodies? In A Cyborg Manifesto Donna Haraway tries

to create a new political perspective. She does so starting from the Cyborg.

This is a cybernetic organism - half nature, half design - without a fixed

identity, a construction, a fiction. In an introductionary essay published

along with the Dutch translation, Karin Spaink makes clear that Cyborgs in a

technical sense cannot yet be constructed, but definitely exist. By bringing

forward elaborate examples she makes it plausible that the self built part of

contemporary man has become a radical part of being human. She states: "The

Cyborg already exists: It's us. We just do not know it yet, because nobody

told us."[12] In other

words, the experience of our body has been changed radically during the ages,

but thinking about it and the socio-political implications which this

thinking gives us, we are not yet conscious of. The man who pretends to be a

woman on Internet is still a hypocrite: he is not a real woman. Female athletes are 'unmasked' by genetic research:

their male chromosomes brutally nullify their feminine characteristics and

self-awareness. However, are these 'exposures' not the final convulsions of

an outlived science? Chimerical

modes of existence

Cyborg or

Chimera, it is not about fictitious models. It is about: "... an

imaginative resource suggesting some very fruitful couplings:"[13]

The Chimera as the feminine 'principle' of which the feminine is immediately

nullified, offers a possibility to make many connections. I have been able to

mention only a few in this argumentation. In a time in which the concept

identity has become problematic I would not only want to draw the 'male'

subject thinking into question. Also the implied oppositional thinking - and

with that 'the' feminine - has to be criticized. With that I do not aim at a

dialectical synthesis like De Cauter ascribes to the hermaphrodite. I propose

an existence within the tension of identity and non-identity. Perhaps we have

to abandon the idea of making a fixed, definite distinction between

man-woman-animal-plant-machine, between artificial and real. The matter of course

with which the male identity would function as a standard measure for all

kinds of non-identities is seriously unsettled. Practically this means that

the conditioned behavior must be deconstructed as far as possible. Flowing

from this an existence could be given shape from the impulses that

continually cross the body and that creates an opportunity to break the

conditioned male-female-heterosexual or homosexual behavior. This is,

however, not about an utopian ideal in which 'mankind' is liberated. At most

about a tale of longing and belonging of man. It is not an option for an

ultimate liberation, but a proposal to accept an existence that was always

artificially created. It is a possibility to affirm this artificiality and

use it creatively, a call for the creating of myths. in that sense perhaps it

is merely a mythomania. Chimerische

gestalten (of een aanzet tot mythomanie)

Mensen houden van eenduidigheid en eenvormigheid. Er is niets zo irritant als iemand die

stelselmatig heersende codes doorbreekt en daarmee in kringen van familie,

vrienden, maar vooral binnen de structuren van de samenleving voortdurend

verwarring zaait. Neem nu Janine Wegman, de bekende Rotterdamse transsexueel,

die door de geautomatiseerde bureaucratie vanwege het vemieuwen van haar paspoort

weer als man door het leven dreigde te moeten gaan. Nu is Janine Wegman niet

eens een voorbeeld van een hemelbestormende genderbender. Zoals zovelen in

haar situatie heeft deze illustere entertainster verkozen om haar verkozen

geslachtelijke rol volledig to leven: ze heeft al jarenlang een monogame

heterosexuele relatie met een mannelijke partner. Met de opkomst

van nieuwe communicatiesystemen als Internet wordt de mogelijkheid geschapen

om op een minder fysiek ingrijpende wijze een identiteit to kiezen. Man,

vrouw, dier, plant, machine, niets staat ons meer in de weg om per dag of per

seconde de avatar te 'worden' die op dat moment bij ons past. En dit alles

zonder dure operaties of anderszins ver strekkende gevolgen. Maar is er in

het geval van de transsexueel of van de cyber-genderbender sprake van een

nieuwe identiteit? Kunnen wij in deze tijd nog spreken van een echte

identiteit of zelfs van een non-identiteit? In een eerder

bestek heb ik verslag gedaan van een interview met de Oostenrijkse schrijfster

Elfriede Jelinek.18 Zij

benadrukt de onmogelijkheid voor de vrouw om zich op talig niveau een

subjectstatus aan te meten. Ze wijst op de gevolgen die dit heeft voor het

(be)schrijven van vrouwelijke lust. Zelfs in een dominante rol blijft de

vrouw object; dat wil zeggen een mannelijke projectie. Jelinek moet daarom

uitgaan van een non-identfteit van de vrouw. Begrijpelijkerwijze is deze

positie voor een vrouw die zich als schrijver tussen haar mannelijke

collega's wil vestigen onverdragelijk. De vrouw als schepper van nieuwe

concepten is en blijft binnen het fallocentrische denken on-denkbaar. Wat te doen? Eén

optie zou kunnen zijn om een nieuwe vrouwelijke identiteit to creëren. Vanuit

de tot nu toe overwegend pejoratief opgevatte 'vrouwelijke' eigenschappen

worden daartoe aanzetten geboden. Hierin schuilt echter het gevaar dat deze

aanzetten nog steeds deel uitmaken van het fallocentristisch denken: er

blijft een scheiding op grond van geslachtelijkheid. Hoogstens dreigt het

fallocentrisme hier te worden vervangen door een 'vaginacentrisme'. Patricia de

Martelaere doordenkt vanuit een lezing van de overigens als zeer mysogyn

geboekstaafde denker Friedrich Nietzsche op interessante wijze de positie van

de vrouw. Zij stelt Nietzsches vrouwvijandigheid ter discussie en kent de

vrouw een bijna paradigmatische positie toe: "Wat de vrouw betekent voor

de man staat in feite model voor wat de hele werkelijkheid betekent voor de

hunkerende sterveling: zij is een fascinatie, een uitdaging en een belofte;

zij is een betoverend spel van schaduwen met de suggestie van een

oogverblindend licht; zij is wispelturig, oogverblindend en vermoeiend - maar

uiteindelijk is zij niets(..).Het is in deze zin dat voor Nietzsche de vrouw,

het wezen dat geen waarheid heeft en ook van geen waarheid wil weten,

op het filosofisch vlak precies de incamatie is van zijn eigen

waarheidgedachte."19 Concluderend

stelt zij dat het geslachtelijke model voor Nietzsches vrolijke wetenschap

noch dat van de man is, noch dat van de vrouw, maar van de hermafrodiet, die

zij als tegenstelling binnen het indidvidu opvat. Lieven de Cauter

bespreekt in Archeologie van de kick de hermafrodiet vanuit een

semiotisch perspectief. Hij dicht het hermafroditische een tekenwaarde toe:

"De hermafrodiet is de personificatie van het neuter, het 'geen

van beide', het neutrum. Men zou hem de neutrale, onzijdige betekenaar kunnen

noemen. Of beter gezegd: de vol-ledige signifiant, tegelijk vol en

leeg."20 Of zoals de Cauter in

een verwijzing naar Jacques Derrida schrijft: "De lege betekenaar,

vacant, brokkelig, veranderlijk, nutteloos." Volgens hem is de

hermafrodiet zo'n lege nutteloze betekenaar: "Hij breekt met het

identiteitsprincipe, de historische basis van onze binaire logica: het principe

van de identiteit (a=a), het principe van de uitgesloten derde (iets is ofwel

a ofwel niet-a), het principe van de contradictie (a= nooit niet-a).(...)Hij

'betekent' uiteindelijk niets anders dan dat hij noch het een noch het ander

is. En toch is hij ook de fata morgana van het 'beide tegelijk', de

mythologische gestalte van de dialectische synthese." Of dit een

dialectische synthese is, wil ik voorlopig in het midden laten. Van belang is

de positiviteit van de tweeslachtigheid, de ambivalentie. Zo biedt de

hermafrodiet in deze interpretaties het zicht op bestaanswijzen die

oscilleren in de spanning tussen een (mannelijke) identiteit en

non-identiteiten. Het zou er dan niet om gaan een nieuwe (tegen) waarheid te

creëren, maar eerder om andere opties - misschien wel: ficties - te

genereren. Wat is

tegenwoordig nog fictie? Laat ik teruggrijpen op ons culturele erfgoed: de

mythe. Is een mythe heden ten dage niet de fictie bij uitstek? Een mythe is

een verhaal over de daden van goden, halfgoden of goddelijke voorouders dat

zich in een mythische oertijd afspeelt, waarin de wereld tot aanschijn komt.

Een mythe kan niet worden ingepast in een historische tijd en een

geografische ruimte: als collectieve overgeleverde ervaring wordt deze

hoogstens middels rituele handelingen in eon historische tijd en ruimte

geplaatst en werkzaam gemaakt. Zo schept de mythe een collectieve identiteit. Wat is er met de

mythe gebeurd? Ten tijde van de Grieken werd de mythische interpretatie

geleidelijk aan verdrongen door een redelijke. Dit hoefde niet

noodzakelijkerwijs tot een conflict to leiden: voor Aristoteles was de ware

philosophos tevens philomythos. De sofisten echter stellen het woord 'mythos'

tegenover 'logos'. Dit wordt als het laatste woord in zijn waarheid vastgesteld

door rationele bewijzen, door het beste argument. In de ontwikkeling van het

westerse denken, waarbij uitgegaan wordt van een accumulatie van kennis,

hebben mythen nog slechts binnen een historische context betekenis. Een

'mythe' is dan een ontmaskerde fabel, een praatje, een onwaar verhaal. Echter, hoe

onwaar is de mythe in een wereld waarin het besef steeds meer doordringt dat

de accumulatie van kennis niet tot

een uiteindelijke samenhang, tot een absolute eenheid leidt. Of, zoals

Jean-François Lyotard het stelt, in een wereld waarin elk vertrouwen in Grote

Verhalen teniet is gedaan, en vermeende religieuze, ideologische en

wetenschappelijke waarheden schijn blijken to zijn. Ik zou uitgaande van

Nietzsches opmerking in Afgodenschemering over "hoe de 'ware

wereld' ten slotte een fabel werd" en zijn conclusie dat "met de

ware wereld wij ook de schijnbare hebben afgeschaft" een voorstel tot

een mythische identiteit willen doen. Chimera:van

mythisch monsterdier naar perverse vrouwelijkheid Bij het ontstaan

van de wereld vindt er een dubbel huwelijk plaats: moeder Aarde trouwt met

haar zoon Hemel en haar zoon Zee. Het eerste huwelijk blijkt vruchtbaar en

harmonisch, het tweede echter - tussen de vruchtbare aarde en de onvruchtbare

zee - disharmonisch. Uit dit huwelijk worden allerlei monsters geboren, hun

kinderen zijn hybriden die op fantastische wijze zijn samengesteld uit

dierlijke en menselijke kenmerken. De Chimera, een achterkleinkind van Aarde

en Zee is het drievoudige dier. Eén van de meest duidelijke beschrijvingen is

van Apollodorus: "Het had een voorste gedeelte van een leeuw, de staart

van een draak, en haar derde hoofd, de middelste, was dat van een geit,

waardoor het vuur spuwde. En het vernietigde het platteland en bestookte het

vee; want het was een wezen met de kracht van drie beesten."21 De Chimera wordt

van oudsher, zoals bijvoorbeeld in de Ilias, beschreven in context van haar

dood. Zij wordt afgeslacht door Bellerophon, die later door zijn overmoed

zelf ten onder gaat. Ginevra Bompiani legt in The Chimera Herself een

interessant verband tussen het woord 'hybris', de zonde die Bellerophons

neergang veroorzaakt, en 'hybrid', het woord waarmee de Chimera wordt

beschreven. Zij stelt dat Bellerophon, door de moord op Chimera,

tegelijkertijd teniet doet wat Chimera in de loop der eeuwen is gaan

representeren: fantasie, poetische genialiteit, droom, illusie, fictie.22 In de mythe van

de Chimera treden dus twee belangrijke elementen op de voorgrond: haar

veelvoudigheid en het illusoire gehalte. Deze hebben blijkbaar iets met

elkaar te maken. Zij voeden een diepgewortelde angst in onze cultuur die door

Paul Diel krachtig wordt verwoord: "The myth externalizes the danger in

the form of a monster encountered by chance. In thruth the

chimerical enemy is always present; every man carries secretly within himself

the temptation of imaginitive exaltation - that is the devouring monster,

Chimera. It is clear that 'chimera' and 'perverse imagination' are

synonymous."23 De Chimera en

haar verontrustende connotaties hebben in de loop der eeuwen een

transformatie ondergaan van mythe naar teken. In moderne tijden wordt ze ten

slotte metaforisch opgevat als slechte muze, als een pervers

vrouwelijk principe. Zoals bij Flaubert in Par les champs et par les

greves, waar zij tegelijkertijd almacht en nihilisme vertegenwoordigt:

alles is mogelijk, niets is van belang. Door haar ongelimiteerde

mogelijkheden wordt zij echter even betekenisloos als Derrida's betekenaar. "In

the last decade of the nineteenth century, the image of the Chimera had

become for poets and writers, as for painters a metaphor for an enigmatic

feminine principle which has the power to attract, conquer and annihilate the

power of the artist."24 Kortom, de

Chimera blijkt een pervers vrouwelijk principe dat geen identiteit inhoudt,

maar wordt opgevat als een illusoire samenstelling van verschuivende

identiteiten. Chimera

als nomadische werking Zegt dit mythisch

beeld iets over bestaanswijzen in onze hedendaagse 'postmoderne tijd'? Is het

meer dan wat in encyclopedieën en woordenboeken terug te vinden is als 'een

mythologisch monsterdier', 'een biologische entbastaard' of 'een

psychopathologische hersenschim'? Zijn er, de vrouwelijke positie als

non-identiteit uit het begin van mijn betoog memorerend, overeenkomsten met

deze positie? Wordt hier een mogelljk eenduidige verwijzing naar het

vrouwelijke overschreden? In ieder geval staat het vrouwelijke niet tegenover

het mannelijke. Ze is hoogstens een telkens verschuivend 'pervers'

principe, dat iedere eenheid doorkruist: "In other words, she contains

the power to nullify any attempt at making sense, and to discourage any

renunciation of it"25 Precies deze

ambivalentie maakt haar tot een lege betekenaar, die het denken verleidt om -

tevergeefs - nieuwe eenduidige betekenissen uit te vinden. Misschien

herkennen we in de eveneens door Nietzsche geinspireerde tekst Nomaden-denken

van Gilles Deleuze een poging om de Chimera om te zetten in een chimerische

denkwijze. Volgens Deleuze tracht Nietzsche op het niveau van denken en

schrijven een dekodering te voltrekken van bestaande kodes, dit wil zeggen

een absolute dekodering of in ruimtelijke termen: deterritorialisering. Deleuze gebruikt

daartoe het prachtlge beeld van Kafka uit De chinese muur : een beeld

van Nomaden die de stad belegeren. Het is het beeld van een nomadische

oorlogsmachine die tegenover de despoot met zijn bestuurlijke machine staat.

De despoot wil koste wat het kost de nomadische machine integreren:

dekoderingen wil hij voortdurend opnieuw vastzetten. Van belang voor

mijn betoog is dat bij Deleuze een denkwijze wordt gegenereerd die bestaande

koderingen steeds opnieuw doorkruist. Deleuze laat daarmee zien dat

eenduidige betekenissen slechts constructen zijn. Weliswaar noodzakelijk voor

het denken, maar onmogelijk als absolute waarheden. Een chimerische denkwijze

incorporeert de openheid die dit denken 'eigen' is. Wat zegt dit

bijvoorbeeld over de in de inleiding genoemde ontwikkelingen op het gebied

van Internet? Biedt dit een perspectief voor een inschatting van de werking

van de nieuwe media? De gender-bending hoeft niet zozeer te worden

gezien als een spel met de hybriditeit van een gegeven identiteit. Het is

meer een chimerisch principe van 'cyberspace': het verdwijnen van de vaste

posities van een actieve producent en een passieve consument, waardoor een

voortdurend verschuiven van posities plaatsvindt. Het zijn chimerische

verschuivingen die ook in het kunstwerk zijn terug te vinden: heterogene

elementen (visuele, geluiden, tactiele etcetera) worden samengebracht in

installaties waarin de ervaring van een eenduidige harmonie tussen lichaam en

geest steeds verschuift. De recipiënt

wordt producent, de producent recipiënt in de doorwerking van het medium. De

oscillatie tussen de subject-object positie door een letterlijke inter-actie,

maakt dat zowel producent als recipiënt onderdeel wordt van 'het' kunstwerk.

Het gaat hierbij niet om dat er iets nieuws gebeurt. Misschien maakt de

conceptuele doorwerking ervan iets duidelijk dat op de een of ander wijze in

kunstwerken en in onze collectieve ervaring al aanwezig is.De fysieke

doorwerking van deze inter-actieve ervaringen, die door recente

ontwikkelingen zo niet veroorzaakt dan toch wordt blootgelegd, is naar mijn

mening hoogst interessant. Hoe gaan wij

'ons' lichaam ervaren? In A Cyborg Manifesto doet Donna Haraway een

poging om een nieuw politiek perspectief te scheppen. Zij doet dit vanuit de

Cyborg. Dit is een cybernetisch organisme - half natuur, half ontwerp -

zonder vaststaande identiteit, een constructie, een fictie. In een inleidend

essay bij de Nederlandse vertaling maakt Karin Spaink duidelijk dat cyborgs

in technische zin nog niet geconstrueerd kunnen worden, maar wel degelijk

bestaan. Aan de hand van uitgebreide voorbeelden maakt zij aannemelijk dat

het zelfgebouwde gedeelte van de hedendaagse mens een ingrijpend onderdeel

geworden is van het mens-zijn. Zij merkt terecht op: "De Cyborg bestaat

allang: wij zijn het zelf. We weten het alleen nog niet, want niemand heeft

ons dat verteld."26 Met andere

woorden: de ervaring van ons lichaam, is in de loop der jaren ingrijpend

veranderd, maar het denken erover en de sociaal-politieke implicaties die dit

denken heeft, daarvan zijn we ons nog niet bewust. De man die zich als vrouw

'voordoet' op Internet is nog een huichelaar: hij is geen echte vrouw.

Vrouwelijke atleten worden 'ontmaskerd' op basis van genetisch onderzoek: met

hun mannelijke chromosomen worden in een klap hun vrouwelijke geslachtelijke

kenmerken en hun zelfbesef teniet gedaan. Maar zijn dergelijk

'ontmaskeringen' geen stuiptrekkingen van een overleefde wetenschap? Chimerische

bestaanswijzen Cyborg of

Chimera, het gaat niet om de fictieve modellen die worden ingezet. Het gaat

om "... an imaginative resource suggesting some very fruitful

couplings:"27 De

Chimera als vrouwelijk 'principe', waarvan overigens het vrouwelijke

onmiddellijk teniet wordt gedaan, biedt een mogelijkheid om vele koppelingen

te maken. Slechts enkele heb ik in dit betoog kort aan kunnen stippen. In een

tijd waarin het begrip 'identiteit' problematisch is geworden, zou ik niet

alleen het 'mannelijke' subjectsdenken ter discussie willen stellen. Ook het

daarin besloten oppositionele denken - en daarmee 'het vrouwelijke - dient bekritlseerd

te worden. Daarmee beoog ik

niet een dialectische synthese zoals De Cauter die verbindt aan de

hermafrodiet. Ik bied een voorstel voor een bestaan in de spanning tussen

identiteit en non-identiteit. Misschien dient het idee dat er een vaststaand

of gefixeerd onderscheid te maken is tussen man-vrouw-dler-plant-machine,

tussen kunstmatig of echt te worden losgelaten. De vanzelfsprekendheid

waarmee de mannelijke identiteit als maatstaf voor allerlei non-identiteiten

zou fungeren komt hiermee op losse schroeven te staan. Praktisch gezien

betekent het dat het geconditloneerd gedrag voor zover dat mogelijk is steeds

opnieuw gedeconstrueerd moet worden. In het verlengde daarvan zou een bestaan

vorm worden gegeven vanuit aandriften die het lichaam voortdurend doorkruisen

en ruimte biedt om de conditionering (mannelijk-vrouwelijk-heterosexueel of

homosexueel gedrag etcetera) to breken. Het gaat echter

niet om een utopisch ideaal waarin 'de mens wordt bevrijd'. Hoogstens om een

verhaal tussen verlangen en belangen van 'de mens'. Het is geen optie voor

een uiteindelijke bevrijding, maar een voorstel een bestaan te aanvaarden dat

altijd al kunstmatig werd gecreëerd. Het is een mogelijkheid om deze

kunstmatigheid te affirmeren en creatief in te zetten, een oproep tot het

scheppen van mythen. In die zin is het misschien niets dan een mythomanie. Terug naar:

|

"By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids

of machine and organism..." [14] Chimaera: 1. v., (Gr.

mythol.)monsterdier; 2. v. (m.) (...ren), entbastaard; 3. meest in de vorm chimère (Fr.),v. (m.)(-s),droombeeld, hersenschim.[15]

"Bizarrerie, vermenigvuldigd en herhaald, waar de modernen

terecht de naam chimera aan gegeven hebben, kan de geest slechts verwarren.."[16] |

NOTES/NOTEN