Bounce > Towards an Aesthetic of a 'Movement'/Naar

een esthetica van een 'Beweging'

|

|

|

Published in English and Dutch in the

catalogue 'Bounce>Rotterdam' on the occasion of an artist-in-residence

project of artists of the Rotterdam artists group 'Kunst en Complex' at the

SNACC in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 1995. The exhibition travelled to

several other galleries in Canada. Bounce > Towards

an Aesthetic of a 'Movement'

(Dutch text

below) Movements,

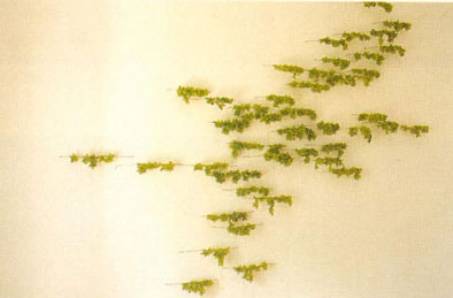

structures and rhythm play an important role in the work of Ellen Dijkstra.

She registers nature in sketches and photographs. By repetitive

patterns of lines, she creates an abstract imagery, permeated with personal

symbolism. The sculptural works following from this, can be described as congealed

movements: literally and figuratively, Ellen Dijkstra casts her

visual images. Repetition,

the basis for her work-process, can also be found in her installations.

Resin, concrete, glass, aluminum or iron are shaped into objects that can be

positioned independently or in infinite sequences of variations. Ellen Dijkstra

is but one of the eleven Rotterdam artists participating in Bounce. For a

period of six weeks they left the relative intimacy of their studios and the

familiar surroundings in exchange for an expectation, composed of experience,

information and fantasy. Depending on the concerns of each artist, solutions

had to be found with respect to their own

work. Each artist was confronted with pre-existing qualifiers. Canada, in the

broadest sense, is the site suggesting a context to define the work. By working

abroad, the artists transposed their customary working conditions. Unforeseen

possibilities and impossibilities announced themselves. Choices were made.

But choices also restrict. New possibilities lead to an adjustment of earlier

made choices. They continuously had to review their expectations. In

Winnipeg, Ellen expected to find a natural environment that could offer her

mosses and tree bark with which she had to create an installation. In Victoria,

the sea would be her starting point. She expected to be forced to speed up

her usually laborious work-process in order to complete her work in a limited

period of time in Canada. That is why she intended to use other than the

usual materials to cast with. While working, she developed all kinds of ideas

about the artistic content and the technique she

intended to apply in Canada. Are these

expectations, ideas and preparations, as well as the working-period in

Canada, not decisive factors in the making of the final result: the exhibited

art work. An affirmative answer would be reason enough to highlight these

elements individually, especially in a catalogue concerning a project like

Bounce. Couldn't we extrapolate this line of thinking and explore the thought

that expectations, ideas and preparations form a substantial part of art

works? Is the 'final' art work not merely a 'congealement' in a movement

that, in fact, never stops? It is seductive to project the metaphor

concerning the substantial and the material aspects of Ellen Dijkstra's art

works to art as such. 1. Bounce

shows the possibilities of a project realized by an artist-initiative outside

the regular institutional channels. There is no sole organizer who curates a

group-exhibition: all parties involved are responsible for the meaning and

the coherence of the works. Here, the artists have regained their own

territory which Daniel Buren states has been gradually yielded to mediocre

artist organizers. They have subjected works to an all-encompassing discourse

of their own, in which the specific expostulations of the individual

participants lose their impact.1 Bounce

does justice to the invisible aspects of the individual work-process without

concluding a theoretical stand in advance or adding a

generalizinglegitimation afterwards. In this regard, Bounce offers an

alternative for the regular group-exhibitions. It fits into a development in

which artists and theoreticians attempt to approach art and theory in a

different manner. An

example of this is Buren who, not only with regard to contemporary exhibition-makers,

but also in a more general sense, criticizes existing art-institutions.

According to him they connect art with power: museums, galleries and salons

decide what art is. In the end, the social context and cultural function of a

work constitute the aesthetic value. Buren

states that most artists take into account the place where the work is to be

displayed, who will give an aesthetic judgment and what the nature of the

aesthetic experience should be - already while making the work. The possibility

of exhibiting the work, its exposibility, determines in advance what the

aesthetic value will be. Possibility creates reality. Following Buren, one

could conclude that the discours of art legitimizes its presence in advance. Buren

criticizes this urge to legitimate because artists make themselves voluntary

slaves to a system. A system that also discourages the spectator or auditor

in his or her creative experience of the work and

limits independent judgment. Both the producer and the consumer are being

limited in their aesthetic choices. Buren states that as long as an artist

works with and within the institutions, he or she cannot remain independent

and no art work will escape this mechanism?2 2. The

French philosopher Jean-FranÁois Lyotard has intensively occupied himself

with Daniel Buren in Que peindre? Adami, Arakawa, Buren.3 He

appreciates Buren's art particularly because Buren introduces a paradox in

his work: a work of art that does not present itself as such, is art. Buren's

art explicitly refers to the possibility of its condition - the institutions

- criticizes these and shows the 'illusion' of its legitimation and its

rules. The apparent paradox lies in the fact that he uses a strict procedure.

In La condition postmoderne4, Lyotard formulates his

alternative for all-encompassing legitimizing discourses: narrative. In

narratives, the gap between concepts and material processes are acknowledged:

matter is thought of an unrepresentable occurrence, an event, both for the

artist and the recipient. This occurrence can only be tacked afterwards by a

narrative, that as a result has no longer the status of a legitimation: it

has become part of the work of art. The paradox given is the following: the

work of art as an event continuously subverts the narrative, but one can only

experience the event by means of a repetition of the material movement in

conceptual frames, materialized in language-games: narratives para-phrase the

material processes literally. Art theory

becomes an interplay of narratives, that are necessarily connected to the

works they only represent apparently, while in fact they are part of their

presence. Narratives lose their expressiveness as soon as

they are applied as general, as conceptual discourses concerning art as such.

Para-phrasing de-legitimizes: a narrative presents the materiality or

corporeality of a work of art. It must abdict its pretensions

of being its sole representative, its exclusive discourse. Lyotard's

way of philosophizing, his language-games move toward literature, that is

towards art, instead of trying to conceptualize its essence. Discourse

as a medium functions the same as avant garde art media. Because of this resonance

one could consider Lyotard's philosophy a form of experimental art: art

subverts the existing rules. Or, in Buren's

terminology: as avant-garde art, philosophy breaks the 'illusion' of

conventional legitimations, that is: of museums. Once we

set a project like Bounce against this background, its specific character

comes to the fore. Bounce shows that the process of production is as valuable

as the final result: art is a continuous flow, a becoming. It also shows that

anticipation and creation of ideas and concepts fulfill a creative function

in this process of becoming. Ideas and concepts do not play a role as

legitimizing discourse. Looking

back on the period preceding the departure to Canada, another characteristic

feature of the project comes to attention: lacking an all-encompassing

legitimization, Bounce does justice to the work-process. The affirmative

answer to the question "Is the `final' result not merely a `congealment'

in a continuous movement?", inevitably contains a shift of attention

from concept to the material presence of art as a non-rule bound process of

becoming. 3. Gilles

Deleuze developed a philosophy of becoming. More so than Lyotard, Deleuze

compares the activity of thought, which always concerns concepts, to the

artistic activity, in which especially percepts and affects of artists and

recipients predominate. From this philosophical point of view, he clarifies

the interaction between concept, percept and affect.5 How

can a becoming or movement be captured in a concept if a concept always

encompasses and identifies? The

concept is a construction which inevitably has a totalitarian impact. In

Deleuze's opinion, however, the core of every concept is an Idea. In contrast

to a concept an Ideas is unlimited, fluid Ideas transcend concepts. Concepts

attest the possibility to know things; Ideas attest the possibility to think

the coherence of concepts. Thought, that is the movement of Ideas, transcend

knowledge: it 'motorizes' conceptualization and keeps it going. This is

why it resonates the becoming which is intrinsic to matter. To think this

paradox really means turning thought against itself, like Buren turns art

against itself. However, as a philosopher, Deleuze acknowledges the necessity

to create concepts, but at the same time he points out that this identifying,

totalitarian thinking, in the final analysis, is an 'illusion'. The event of

matter is excluded as soon as conceptuality becomes decisive in determining

art. The paradoxical movement art consists of can only be thought to be the

subversion of concepts by means of Ideas. What

happens when we apply this Deleuzian view of (self-reflexive) conceptuality

to the art practice? Ideas are

cast into sculptures. The spectators are moved by experiencing these

sculptures. In this way, the experience of an art work is composed of a

clustering of affects and percepts - that is to say by sensations - and

concepts that trigger ideas. Finally, the aesthetic experience of the work

transcends every conception. Yet it creates understanding. Bounce

bares witness to the fact that conceptual considerations change in the

process and the process changes by conceptualizing it. Bounce opens the

eyes of the spectator to the complete dynamics of art-practice. The

expectations, ideas and preparations, the actual developing of the work and

its presentation in Canada cannot be seen anymore as a secondary activity to

which meaning is allocated afterwards. Bounce shows that every movement in

art, that is, every institutionalized, artistic

trend, in the first and last instance is movement to be moved by. NOTES 1. Koen

Brams, "An Exhibition is a Place to Exhibit. Interview with

Daniel Buren", in Witte de With Cahier 3, Rotterdam 1995. 2. Marie-Louise Sering, Kunst in Frankreich seit 1966, Zerborstene

Sprache, zersprengte Form, Cologne 1986. 3.

Jean-FranÁois Lyotard, Que peindre: Adami, Arakawa, Buren, Paris 1987. 4.

Jean-FranÁois Lyotard, La condition postmoderne-rapport sur le savoir,

Paris 1979. 5. Gilles

Deleuze and Felix Guattari, What is philosophy? London/New York 1994. Back

to:

Bounce > Naar een esthetica van een 'Beweging' Bewegingen, structuren en ritme van land-schappen spelen

een grote rol in bet werk van Ellen Dijkstra. In schetsen, maar ook

fotografisch, registreert zij natuur. Door herhaling van lijnen ontwikkelt

zij een geabstraheerde beeldtaal, doortrokken van een persoonlijke symbo- liek. De sculpturale werken die daaruit voortvloeien, zijn

te omschrijven als gestolde bewegingen: letterlijk en figuurlijk giet

Ellen Dijkstra haar visuele beelden. Herhaling, de basis van haar werkproces, keert ook terug

in haar installaties. Hars, beton, glas, aluminium of ijzer wordt gevormd tot

objecten, die afzonderlijk, of in een in principe

oneindige reeks van variaties, opgesteld kunnen worden. Ellen Dijkstra is slechts ťťn van de elf Rotterdamse

kunstenaars die deelnamen aan Bounce. Gedurende een periode van zes weken hebben zij de relatieve geborgenheid van hun atelier en

vertrouwde omgeving verwisseld voor een verwachting, opgebouwd uit

ervaringen, informatie en fantasie. Afhankelijk van ieders afzonderlijke

belangen moesten er oplossingen gevonden worden, met inachtneming van de

eigenachtergrond. Elke kunstenaar werd geconfronteerd met de reeds bestaande

situatie. Canada, in de breedste zin van bet woord, werd de context

waarbinnen bet werk gedefinieerd moest worden. Dit bracht de noodzaak met

zich mee om de geŽigende werkomstandigheden te herzien. Onvoorziene

mogelijkheden en onmogelijkheden dienden zich aan. Keuzes werden gemaakt. Keuzes

beperken echter ook. Nieuwe mogelijkheden leidden tot een aanpassing van

eerder gemaakte keuzes. Voortdurend hebben zij hun standpunten moeten

bijstellen. Zo verwachtte Ellen in Winnipeg een natuurlijke omgeving

aan te treffen die haar mossen en boomschors zou leveren, op basis waarvan

zij een installatie zou kunnen maken. In Victoria zou de zee haar

uitgangspunt vormen. Ze verwachtte dat haar doorgaans tijdrovende werkproces

versneld zou moeten worden om in een beperkte periode, in Canada, haar werken

te kunnen realiseren. Daarom koos zij voor andere dan de gebruikelijke

gietmethode. Allerlei inhoudelijke, vormtechnische en artistieke ideeŽn

werden ontwikkeld om deze in Canada te kunnen realiseren. Is het niet zo dat deze verwachtingen, ideeŽn en

voorbereidingen, naast de werkperiode in Canada een beslissende invloed

uitoefenen op het uiteindelijke resultaat, het geŽxposeerde kunstwerk? Een

bevestigend antwoord zou reden genoeg zijn om juist in een catalogus van een

project als Bounce deze elementen te belichten. Maar zouden we niet nog een stap verder moeten gaan en

moeten vaststellen dat verwachtingen, ideeŽn en voorbereidingen een

substantieel onderdeel vormen van kunstwerken? Of anders geformuleerd: Is het

'uiteindelijke' kunstwerk niet slechts een 'stolling' in een beweging die in

feite nooit stopt? Mogen we de beeldspraak over inhoudelijke en materiele aspecten van Ellen Dijkstra's

kunstwerken uitbreiden tot de kunstbeschouwing als zodanig? 1. Bounce laat zien wat er mogelijk is als er vanuit

kunstenaarsinitiatieven, dus buiten de reguliere institutionele kanalen om,

een project wordt gerealiseerd. Er is geen 'sole organiser' die een

groepstentoonstelling samenstelt: alle betrokkenen zijn verantwoordelijk voor

de betekenis en de samenhang van de werken. De kunstenaars hebben hiermee een

eigen territorium teruggevorderd waarvan Daniel Buren stelt dat dit

geleidelijk is afgestaan aan middelmatige 'artists organisers'. Zij hebben

werken onderworpen aan een door hen ontwikkeld overspannend discours, waarin

de specifieke vertogen van afzonderlijke deelnemers hun impact verliezen.1 Bounce doet recht aan nagenoeg onzichtbare aspecten van

het individuele werkproces zonder van te voren een theoretische stellingname

in te nemen of er achteraf een veralgemeniserende betekenisgeving als legitimatie op te plakken. Ook

daardoor biedt Bounce een alternatief voor de reguliere

groepstentoonstelling. Zij past hiermee in een ontwikkeling, waarin

kunstenaars en theoretici pogen om kunst en theorie op een andere wijze te

benaderen. Een voorbeeld hiervan is Daniel Buren, die niet alleen ten

aanzien van hedendaagse tentoonstellingsmakers, maar ook in meer algemene zin

bestaande kunstinstituties bekritiseert. Zij verbinden volgens hem kunst met

macht: musea, galeries en salons bepalen wat kunst is. Uiteindelijk

constitueren maatschappelijke context en culturele functies van een werk de esthetische waarde ervan. Het valt aan te nemen,

meent Buren, dat de meeste kunstenaars er al tijdens het maken van het werk rekening mee houden waar het komt te hangen, wie er een

esthetisch oordeel over gaat geven en wat de aard van de esthetische ervaring

zal zijn: de exposeerbaarheid van het werk bepaalt vooraf de esthetische

waarde ervan. De mogelijkheidsvoorwaarde creŽert de realiteit. Er zou met

Buren gesteld kunnen worden dat het 'vertoog' van de kunst bij voorbaat

legitimerend werkt. Buren bekritiseert deze legitimatiedrang. Kunstenaars

maken zich hierdoor vrijwillig tot slaaf van een systeem, dat bovendien de

toeschouwer of toehoorder in zijn of haar creatieve ervaring van het werk

ontmoedigt en het zelfstandig oordeelsvermogen inperkt. Zowel producent als

consument worden in hun esthetische bewegingsvrijheid beperkt. Buren meent

dat zolang hij of zij met en binnen de instituties werkt, geen kunstproducent

onafhankelijk kan blijven en geen kunstwerk aan dit mechanisme zal

ontsnappen.2 2. De Franse filosoof Jean-FranÁois Lyotard heeft zich in Que

peindre? Adami, Arakawa, Buren intensief met het werk van Daniel Buren beziggehouden.3 Hij waardeert Burens kunst met name

omdat deze een paradox in zijn werk binnenvoert: alleen datgene wat zich niet

meer als zodanig presenteert, is kunst. Burens kunst

expliciteert haar mogelijkheidsvoorwaarde - de instituties -, bekritiseert

deze en toont de illusie van haar legitimatie en haar regels. Lyotard formuleert in La condition postmoderne4

een alternatief voor overkoepelende legitimerende verhalen: kleine verhalen.

In deze kleine verhalen wordt de kloof tussen concepten en materiele

processen erkend: materie wordt gedacht als een niet-representeerbare

gebeurte- nis, zowel voor de kunstenaar als de recipiŽnt. Deze gebeurtenis kan alleen achteraf door een klein

verhaal 'gegrepen' worden, dat dien ten gevolge niet langer de status van een

legitimatie kan opeisen: het is deel van het kunstwerk geworden. Dit

levert de volgende paradox op: het kunstwerk als gebeurtenis ontwricht

voortdu- rend het kleine verhaal, maar men kan slechts de gebeurtenis

ervaren met behulp van een herhaling van de materiŽle beweging binnen conceptuele

kaders, gematerialiseerd in taalspelen: kleine verhalen om-schrijven

het materiŽle proces letterlijk. Kunsttheorie verwordt daarmee tot samenspel van kleine verhalen,

die noodzakelijkerwijs gebonden zijn aan de werken die zij slechts ogen- schijnlijk re-presenteren, terwijl zij in feite

deel uitmaken van hun presentie. Deze kleine verhalen raken ontwricht, zodra

ze toegepast worden als zijnde algemeen geldend, als conceptuele vertogen over het wezen van de kunst. Om-schrijvingen

de-legitimeren: kleine verhalen stellen de 'werkelijkheid' van de

materie present zonder de pretentie dat zij de enige representatie, een

exclusief vertoog zijn. Bij Lyotard bewegen de taalspelen zich naar de

literatuur toe, een beweging naar kunst in plaats van een poging haar

essentie te conceptualiseren. Het vertoog als medium functioneert op dezelfde

wijze als avant garde kunstmedia. Vanwege deze resonantie zou men Lyotards

wijze van filosoferen als een vorm van experimentele kunst kunnen opvatten:

kunst die de bestaande regels ontwricht. Of, in Burens terminologie: net als

avant garde kunst, doorbreekt filosofie de illusie van conventionele

legitimaties, dat wil zeggen die van musea. Als we een project als Bounce tegen deze achtergrond

plaatsen, treedt haar specifieke karakter naar de voorgrond: Bounce toont in

haar praktische invulling dat het produktieproces even

waardevol is als het uiteindelijke resultaat: kunst is een continue stroom,

een worden. Het toont ook dat de anticipatie en creatie van ideeŽn en

concepten een creatieve functie vervullen in dit wordingsproces. IdeeŽn en

concep- ten spelen geen rol als legitimerend discours. Vanuit deze gedachte terugkijkend op de periode

voorafgaand aan het vertrek naar Canada treedt een tweede specifiek kenmerk

van Bounce naar voren: naast het ontbreken van een

overkoepelende legitimatie wordt recht gedaan aan het werkproces. Het

bevestigende antwoord op de vraag "Is het 'uiteindelijke' kunstwerk niet

slechts een 'stolling' in een voortgaande beweging?" houdt

onvermijdelijk een verschuiving van de aandacht van de materiŽle aanwezigheid

van het kunstwerk naar een nog niet door regels gebonden wordingsproces. 3. Gilles Deleuze ontwikkelde een filosofie van het worden.

Meer dan Lyotard probeert hij de denkactiviteit, waarin het altijd om

concepten draait, te vergelijken met de artistieke activiteit,

waarin vooral percepten en affecten een rol spelen. Vanuit zijn filosofische

perspectief probeert hij het zicht op de wisselwerking tussen concept,

percept en affect te openen.5 Hoe kan, zo vraagt Deleuze zich af, in een concept dat

altijd totaliserend en identificerend werkt, een worden of

beweging worden gedacht? Het concept is een denkconstructie waarvan

onvermijdelijk een totaliserende werking uitgaat. Deleuze meent echter dat de

kern van ieder concept een Idee is. In tegenstelling tot een concept is een

Idee onbegrensd, fluide. IdeeŽn overstijgen concepten. Gaat het bij concepten

om de mogelijkheid om dingen te kennen, bij IdeeŽn gaat het om de mogelijkheid

hun samenhang te denken. Het denken, dat wil zeggen de beweging van Ideeen,

overstijgt kennis: het is datgene wat het conceptualiseren in werking zet en

houdt. Zo resoneert dit het worden dat eigen is aan de materie. Deze

paradox te denken betekent eigenlijk het denken tegen zichzelf opzetten,

zoals Buren de kunst tegen zichzelf opzet. Deleuze erkent als

filosoof wel degelijk de noodzaak om concepten te hanteren, maar geeft tegelijkertijd

aan dat dit identificerende, totaliserende denken een 'illusie' is. Het

gebeuren van de materie wordt uitgesloten zodra het doorslaggevend wordt bij

de bepaling van wat kunst is. De paradoxale beweging binnen de kunst kan

slechts worden gedacht door de ontwrichting van concepten vanuit IdeeŽn. Wat gebeurt er wanneer we deze deleuziaanse opvatting van

(zelfreflexieve) conceptualiteit toepassen op de kunstpraktijk? IdeeŽn worden door kunstenaars in beelden gegoten. Door

deze beelden worden de toeschouwers geraakt. Het ervaren van een kunstwerk wordt

vervolgens bepaald door een clustering van affecten en percepten - dat wil

zeggen door sensaties - en concepten die IdeeŽn raken. Uiteindelijk gaat de

esthetische ervaring van het werk gaat alle begrip te boven en toch creeert

het een begrijpen. Bounce laat zien hoe conceptuele overwegingen het proces

veranderen en hoe het proces verandert door het te conceptualiseren. Bounce

opent onze blik voor de volledige dynamiek van kunstpraktijken. De

verwachtingen, ideeŽn en voorbereidingen, het feitelijke ontwikkelen van het

werk en de presentatie ervan in Canada kunnen niet meer gezien worden als

secundaire activiteiten die pas betekenis achteraf krijgen. Wat Bounce in ieder geval toont, is dat iedere beweging

in de kunst, dat wil zeggen iedere geÔnstitutionaliseerde, artistieke

school in eerste en laatste instantie een beweging is om bewogen

door te worden. NOTEN 1. Koen

Brams, "An Exhibition is a Place to Exhibit, Interview with Daniel

Buren", in Witte de With Cahier 3, Rotterdam 1995. 2. Marie-Louise Sering, Kunst in Frankreich seit 1966.

Zerborstene Sprache, zersprengte Form, Keulen 1988. 3.

Jean-FranÁois Lyotard, Que peindre? Adami, Arakawa, Buren,

Parijs 1987. 4.

Jean-FranÁois Lyotard, La condition postmoderne - rapport sur le savoir,

Parijs 1979. 5. Gilles

Deleuze en Felix Guattari, What is philosopy? Londen/New York 1994. Terug naar:

|

Ellen

Dijkstra "A

bright spot in the woods" (fragments) mixed media installation @ SNACC Winnipeg

Joep

van Lieshout "La

Bais-o-DrŰme" Polyester

sandwich construction 7x2.20x2.20 @

Open Space, Victoria

Ellen

Dijkstra "A

bright spot in the woods" mixed media installation @ SNACC Winnipeg

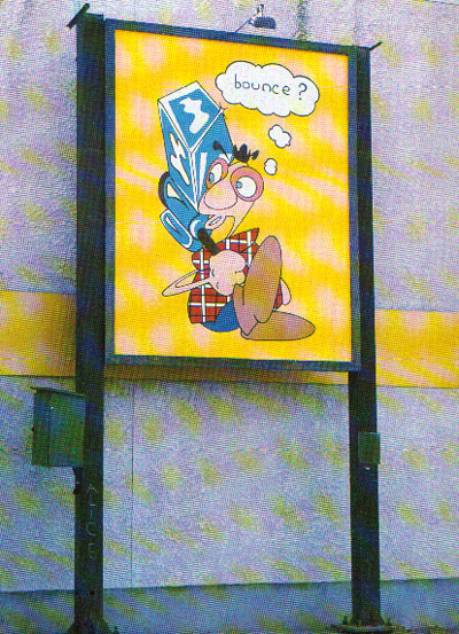

Rop de

Graaf "Dissentiant

quod recte sentio" Plug-in

billboard at River and Osborne, Winnipeg |